In days of yore (i.e., before the Internet), historians faced formidable constraints on conducting research. If one did not have the means to travel to Oxford University, for example, then exploring the depths of their archives was not an option. In 2013, University of New Mexico (UNM) doctoral candidate Chris Steinke faced no such obstacles, and with the help of modern technology, he landed on a far-reaching historical discovery.

Now an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, Steinke was working on his dissertation at UNM when he happened upon a map.

“I had been writing about and researching some indigenous leaders and delegates who had traveled from the Great Plains down to St Louis, one of whom was an Arikara leader,” Steinke says.

The map in question was not, however, among the historical records on the UNM campus. Steinke found it through an online archive of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, and swiftly discerned its significance.

“It wasn’t completely identified as a map from this Arikara leader, but looking at it for a few minutes, I pretty quickly realized that’s what it was,” says Steinke. “It was, in fact, a map by this Arikara leader, and it included one spelling of his name on top of the map.”

That name is Inquidanécharo, a variation of an Arikara word meaning "band chief" or "chiefly village." Inquidanécharo is one of several names given to the Arikara leader Too Né, who traveled with Lewis and Clark during their expedition and then visited Washington, D.C., where he died from illness in 1806.

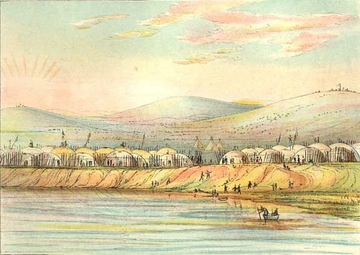

Drawn by Too Né sometime in 1805 or early 1806, the map depicts the course of the Missouri River as it runs alongside more than thirty different Native American groups and significant places in the history of the Arikara people. It also features two different campsites of Lewis and Clark along the Missouri River, one in present-day North Dakota and one in present-day South Dakota.

“The more I looked at it,” Steinke says, “I realized it was not a map that any historian had really written about, especially in the U.S. Basically, it was unknown to historians of the Lewis and Clark expedition. I was very, very surprised to see it, and surprised that it was in France as well.”

Steinke had accessed the online archives at the Bibliothèque Nationale because he was looking for documents from the French colonial period, from the 17th and 18th centuries. To unearth a map from the early 19th century, following the Louisiana Purchase, was wholly unexpected.

“From that point forward, it really just became a question of trying to figure out how it got there and what it was saying,” Steinke says, “and figuring out what the significance of the map was.”

The consensus among academics now, as stated in articles published by sites such as the History News Network and Alternet, is that Steinke’s discovery is significant not only for historians but in how it changes our understanding of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

According to History.com, in 1804 Meriwether Lewis was tasked by President Thomas Jefferson with “exploring lands west of the Mississippi River that comprised the Louisiana Purchase.” Lewis then selected William Clark to accompany him on this journey, and they spent more than two years traversing roughly 8,000 miles.

This is how most of us learn about Lewis and Clark, with the focus on what Steinke calls the “east/west view” of the expedition, which is the very concept the map challenges.

“So instead of looking east from Monticello to the rest of the United States at the time,” says Steinke, “the map really shows Lewis and Clark right in the center of Native North America.”

This is significant because it “shows Lewis and Clark entering a complex indigenous region,” Steinke says, “an indigenous political landscape where they were negotiating not just with Native peoples who they met along the Missouri River, but many other indigenous leaders and diplomats from across the Great Plains region.”

Steinke says the map invites historians to rethink the bilateral view of diplomacy that has until now been the standard when studying Lewis and Clark.

“It (the map) is not just looking at American diplomacy with Native peoples as this kind of two-sided proposition,” Steinke says, “but rather looking at a multilateral indigenous diplomacy where you have a number of different nations in this region negotiating with one another.”

In addition to various tribes and locations, the map also marks areas described in Arikara oral traditions, such as “the turtle that carried 56 men and drowned them.” As the story goes, a group of young men came across an enormous snapping turtle, and all but one of the young men climbed onto the turtle’s back. He was in awe of the turtle and felt it was a holy thing that should be respected. Instead of climbing on, this young man walked beside the turtle as it carried his companions. The turtle made a turn and headed toward a lake. The young men tried to jump off before the turtle reached the water, but their feet were stuck on the turtle’s shell. They remained stuck to the turtle’s back as it carried them under the water.

That night, the young man who had walked beside the turtle sat by the bank of the lake and wept, mourning the loss of his friends. In the morning, one of the young men who had gone under with the turtle came to the surface of the lake. He told his friend to return home and relay the story of the turtle to the people in their village, and that from then on, “Whatever you desire, come here and tell us. Now we’ll watch over you as you go around.”

“That particular oral tradition really reflects the extent to which this map shows Arikara history and the depth of their history in the Great Plains and in this region,” Steinke says.

As for how this map drawn by an Arikara leader traveling with Lewis and Clark ended up at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, that part of the narrative remains somewhat of a mystery.

“I never quite pieced together the full story,” Steinke says. What he calls his “best guess,” Steinke summarizes in a paper for the William and Mary Quarterly, titled “Here is my country”: Too Né's Map of Lewis and Clark in the Great Plains.” The excerpt reads:

It (the map) probably left the United States in 1822 with Jean-Guillaume Hyde de Neuville, a French diplomat in Washington, and his wife, Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, who was one of the first artists to portray Native subjects in any detail. During a visit to Jefferson at Monticello or an encounter with his former chef, Julien, they acquired Too Né’s work. Brought back to France as a souvenir, the map stayed in the family until 1905, when Hyde de Neuville’s niece donated it to the Bibliothèque nationale. (Steinke, William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 71 No. 4, p. 609)

Dedicated to deepening our understanding of what was happening in the Great Plains before Lewis and Clark, and before American expansion, the discovery of Too Né’s map was significant for Steinke.

“The map provides a picture of the Great Plains leading up to Lewis and Clark, and the very deep history of the region before American expansion,” Steinke says. “In that sense it was very important to me to try and understand this map and what it said about Great Plains history, not only at the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, but also in the centuries before that, leading up to 1804, really showing that complex history before the Americans arrived.”

An English language version of the map is now available, as is the digitized copy of the original map found in the online archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.