In a world overrun with social media headlines, breaking news alerts and media sensationalism, it is easy to lose sight of the need for basic humanity. That is why The University of New Mexico Refugee Well-Being Program is working to connect students with refugees starting their new lives in Albuquerque.

“Without this program, I would not be where I am today,” said Desire Kasi, a Congolese refugee. “This program helped me to start my life.”

“I thank god for this project. It changed my life,” Antoinette Bifuko added.

Desire Kasi and his wife Antoinette Bifuko are adamant that the UNM Refugee Well-Being Program (RWP) helped them survive their immigration from Africa. They battled assault, military suppression, language barriers and mental and physical anguish to reach freedom.

"If I had been through the things they’ve been through, I wouldn’t have had what it takes to survive." - Kelle Aycock, RWP student

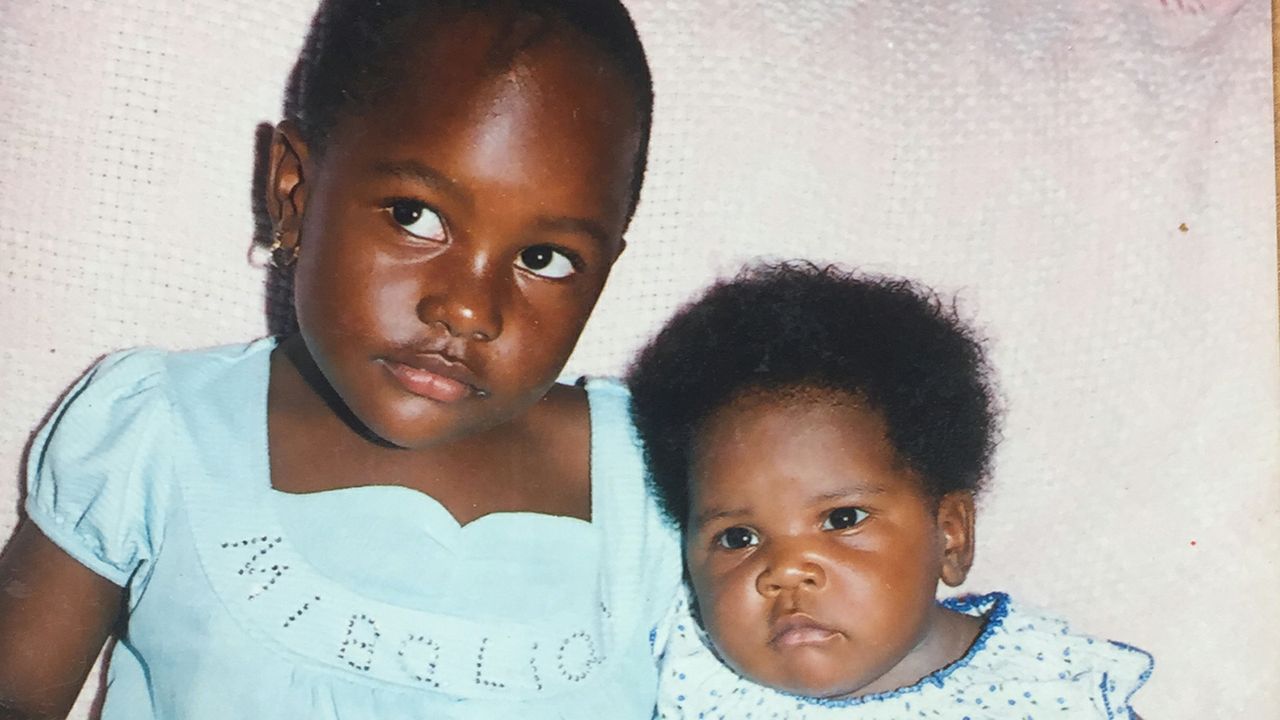

The two fled from the Democratic Republic of Congo to a refugee camp in Uganda. But that didn’t erase the memories of cruel rebel soldiers who assaulted women, including Antoinette. Since there was not enough food in the camp, the couple lost a considerable amount of weight. What little sustenance they had, they gave to their children. But it still wasn’t enough, and their young daughter died while the family struggled to survive.

Kasi, Bifuko and their six other children were finally able be resettled in the U.S. They thought they were leaving their troubles behind them, and were eager to pursue the endless opportunities they’d heard existed in America.

But once they arrived, their situation didn’t get any better. In fact, it got worse. They were plagued with a new onslaught of challenges.

“I looked at my life and my family, and thought we should have just stayed in Africa,” Kasi said. “I thought it would be better to have died than continue living the life we were faced with in America.”

The couple says the agency in charge of helping them settle in Albuquerque didn’t do a very good job. The organization helped them find a house, but did little else to ensure their successful transition into American life. Kasi and Bifuko didn’t know where the grocery store was, they didn’t have any food, neither of them spoke English; and soon after they arrived, they found out Bifuko was pregnant. Being unable to understand American culture or society, they didn’t know how to use the local transportation system or how to get medical care for her. Plus, in Africa, they had learned if they admitted to needing help, they’d be shot.

Without proper medical care and nutrition, Bifuko had a miscarriage.

“When I came to America, I thought things would change. But then I realized, we’d be miserable here too,” Bifuko said. “I was confused about why the miscarriage happened, and didn’t understand why life here still seemed so dangerous.”

The two nearly drown in depression and anxiety. They couldn’t figure out how to find their place in this new world that was supposed to be filled with so much possibility. For a year they struggled with their new life. Then a local refugee community leader and interpreter for the UNM Refugee Well-being Project introduced them to the program. Martin Ndayisenga was himself once a refugee in the program, and knew the difficulties of restarting life in a new culture.

“It’s really about building these relationships on an equal basis. Not just seeing them as poor refugees who we have to help, but recognizing all that they bring to our world.” said Jessica Goodkind, project director at RWP. “They bring a lot. They’re survivors, they made it this far, and they’ve gone through more than most people will go through in a lifetime.”

About 70,000 refugees come to the United States each year; on average about 250-300 are resettled in Albuquerque. Federally funded refugee-specific support ends after about four months for most families. After four months, refugees are expected to be economically 'self-sufficient'. However, the challenges that refugees face in becoming self-sufficient are not attainable for most families in four months. Which is why programs like the Refugee Well-being Project are necessary. They allow researchers, service providers and advocates to work together to develop initiatives that support refugees, and to advocate for public policies that reflect realistic expectations from refugee families.

The RWP, part of the UNM Sociology Department, is a 9-month program that pairs undergraduate students with newly arrived refugees. Students commit to two semesters, during which they learn about how to mobilize community resources.

The students also engage in mutual learning, which enables them to learn about refugees’ cultures, experiences and knowledge. Refugees then feel more valued by the community, and also learn basic skills to operate in their new country.

“To see their resiliency is eye-opening,” student Kelle Aycock said. “I think if I had been through the things they’ve been through, I wouldn’t have had what it takes to survive.”

In Kasi and Bifuko’s case – the program was life-change, and life-saving. The couple was introduced to Kelle Aycock, a UNM student taking the refugee well-being class. Aycock was paired with Kasi and Bifuko, and was charged with helping them navigate their new country. She started by showing them where to buy groceries, and how to function in American society day-to-day.

“This framework of mutual learning is pretty unique. UNM is one of the only places in the country that offers both mentorship and advocacy,” Goodkind said. “It’s not just a project that is helping refugees, but it’s really valuing what refugees’ knowledge and language and culture bring to our country.”

“Spending the time with them and hearing all the trauma they went through to be here, changed the course of my life,” Aycock said. “I wanted to become a counselor, but after spending time with Antoinette-- I understood my calling is to work with women who’ve been through severe trauma.”

When she realized neither spoke English, Aycock helped Kasi enroll in a language class. She and other students also helped their children learn English, and complete necessary schoolwork. Then she encouraged Kasi to enroll in classes to become a Certified Nurse Assistant.

With help from Aycock’s medical friends and the refugee community, Kasi was able to take his board exam after just two months of studying. He passed, found a job and was finally able to pursue the opportunities he’d long heard were possible in the United States; and along the way, made lifelong friends and a new community.

“I got a new family,” Aycock said.

“She was our angel,” Kasi added.